There are smart destinations and there are stupid ones in major gifts.

Jeff and I experienced one situation in which the Director of Development and all of her MGOs had only one objective for each donor on each caseload: to build relationships with donors and not ask for money.

Now the first part of that objective isn’t too bad – to build relationships. That is a smart destination. But the second part – not asking for money – is really stupid. It’s no wonder that each of the caseloads in the care of these MGOs and their Development Director was in such horrible shape that someone should have been fired.

When we asked why they had added the bit about not asking for money, the DOD said, “Well, if we build solid relationships, then the money will come.” We pointed out that the money hadn’t come and asked if they had really built solid relationships or was there something else missing – like asking?

The look on the DOD’s face could have won an Oscar. It was as if asking was a foreign concept. I think you will agree with me that everything about this situation was stupid and ignorant.

Which brings me to a core question that every manager of major gifts and every MGO should have a proper answer to – What is THE critical objective of major gifts? Put simply, it’s:

To secure funds for the organization by

fulfilling the interests and passions of key donors.

Jeff and I have been talking quite a bit about what it means to fulfill the passions and interests of donors – the key reason a donor parts with his or her money. Call this side of the caseload coin “the passions and interests dynamic” – the donor centered side of the coin. If you don’t do things properly here you will lose the donor.

The other side of the coin is the organizational side – the economic side. If you don’t do things right here you will lose money.

Think about this for a second. There are two things you are trying to do in your caseload work – fulfill donors needs and passions AND secure funds to operate your programs and the organization.

I find that way too many managers focus on the first part and not the second, which is why you have well meaning DOD’s like I mentioned at the top of this post. They spend their time building relationships and not raising money and feeling good about it.

This just does not work. And often, MGOs and their managers hide behind the relationship thing as an excuse not to raise money. This is not right and should not be allowed to continue. The fact is that the quantifiable goal of an MGO is to raise money. Period. If you don’t do that (at an acceptable ROI), then you are failing.

So, all this to say… a caseload has its own mini economy that must be managed for organizational purposes.

I like to look at that economy in a couple of ways.

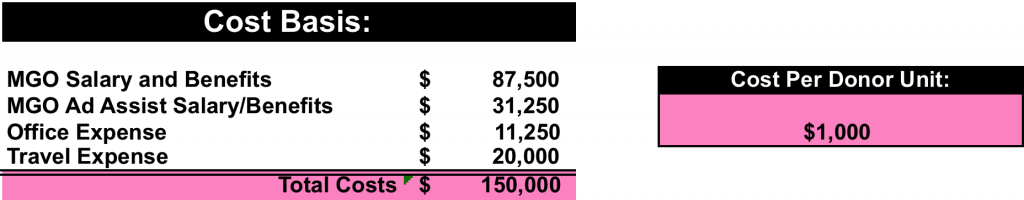

First, the cost side:

Let’s say these are the operating costs of one MGO in a medium sized non-profit. If your numbers are different, use these categories to figure out your annual costs. Let’s also say there are 150 qualified donors on the caseload. Now note that the cost to service ONE donor is $1000 a year.

This is an important figure to keep in mind. Here’s why. If an MGO clearly understands that there is a REAL cost to relate to one donor, that MGO will realize that there is an economic consequence to not taking care of the donor. It actually costs the non-profit money! This is an important data point for an MGO and his/her manager.

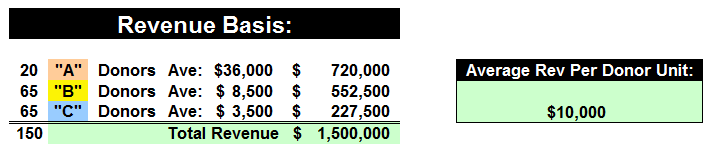

Next, the revenue side:

Let’s say the qualified caseload breaks down into A, B, C donors as I have designated in the chart above. Several things to note here. There are fewer A donors, but they have higher value; the caseload value is $1.5 million, and; the average revenue per donor is $10,000.

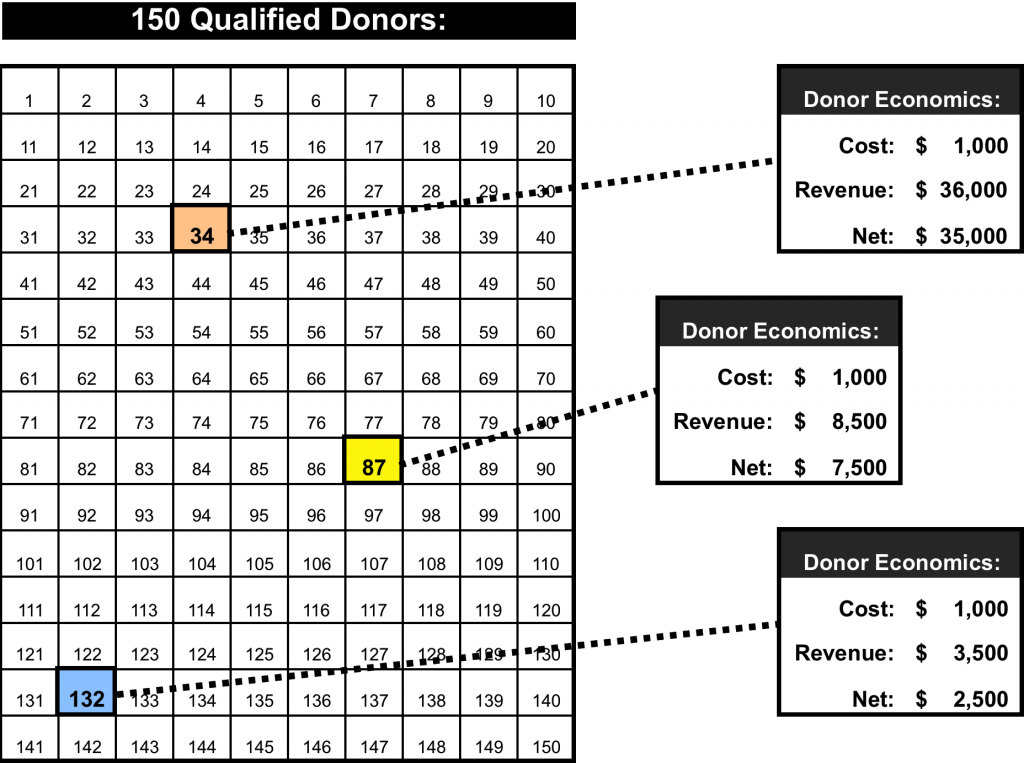

Now, putting cost and revenue together, take a look at this chart:

Here are the 150 qualified donors: some of greater value – others of lesser value. They each cost, on average, $1000 to service. And the net revenue from each is different.

Now, one sharp-eyed critic, upon seeing this chart, pointed out that the cost to service an A donor would be higher than a B donor etc., making the ratios turn out differently. This is true and you can adjust the math to allocate cost properly.

But here are the points I want to communicate to you in this post:

- An MGO should understand that it costs money to manage a donor. Real money. If he understands this it should motivate him to steward his time and efforts to manage each donor on his caseload.

- An MGO should understand that the donors must yield revenue in excess of what it costs to service them or there will be nothing left to give to the organization. There are exceptions to this. For instance, you are managing a relationship that will take two or three years to reach its potential. In this case you may lose money for a time before getting into a positive net revenue situation. But be sure there is real potential there. I have seen too many situations where an MGO chases a high capacity donor only to have wasted time and money.

- An MGO needs to walk away from a situation where the donor gets what she wants but the organization doesn’t. This one is difficult. But it is true. You cannot be in a one-sided relationship with a donor where everything is going her way, but very little, in terms of economic return, is coming to the organization. It is not good stewardship. It is not what you are hired to do. And further, it is not right.

So, a smart destination for caseload and donor management is to have relationships with donors where:

- The donors get their passions and interests fulfilled.

- Net revenue results from that relationship that funds the programs and operations of the organization.

- And all this is accomplished at a reasonable ROI (return on investment).

Do not let yourself love either side of the caseload coin more than the other. You must deliver on both sides. As a professional MGO, you must deliver on fulfilling donor passions and interests AND you must deliver on securing revenue for the organization at a proper cost.

You cannot do one at the expense of the other.

Richard

I just wanted to let you guys know I read your blog each morning and find it inspiring and educational. Keep up the good work and thank you for sharing so much good information.

Thanks for the kind words, Stephen. We really appreciate it.