One of the most frustrating behaviors I’ve encountered in my career in fundraising is people (of every type) covering up the need that their non-profit exists to address.

One of the most frustrating behaviors I’ve encountered in my career in fundraising is people (of every type) covering up the need that their non-profit exists to address.

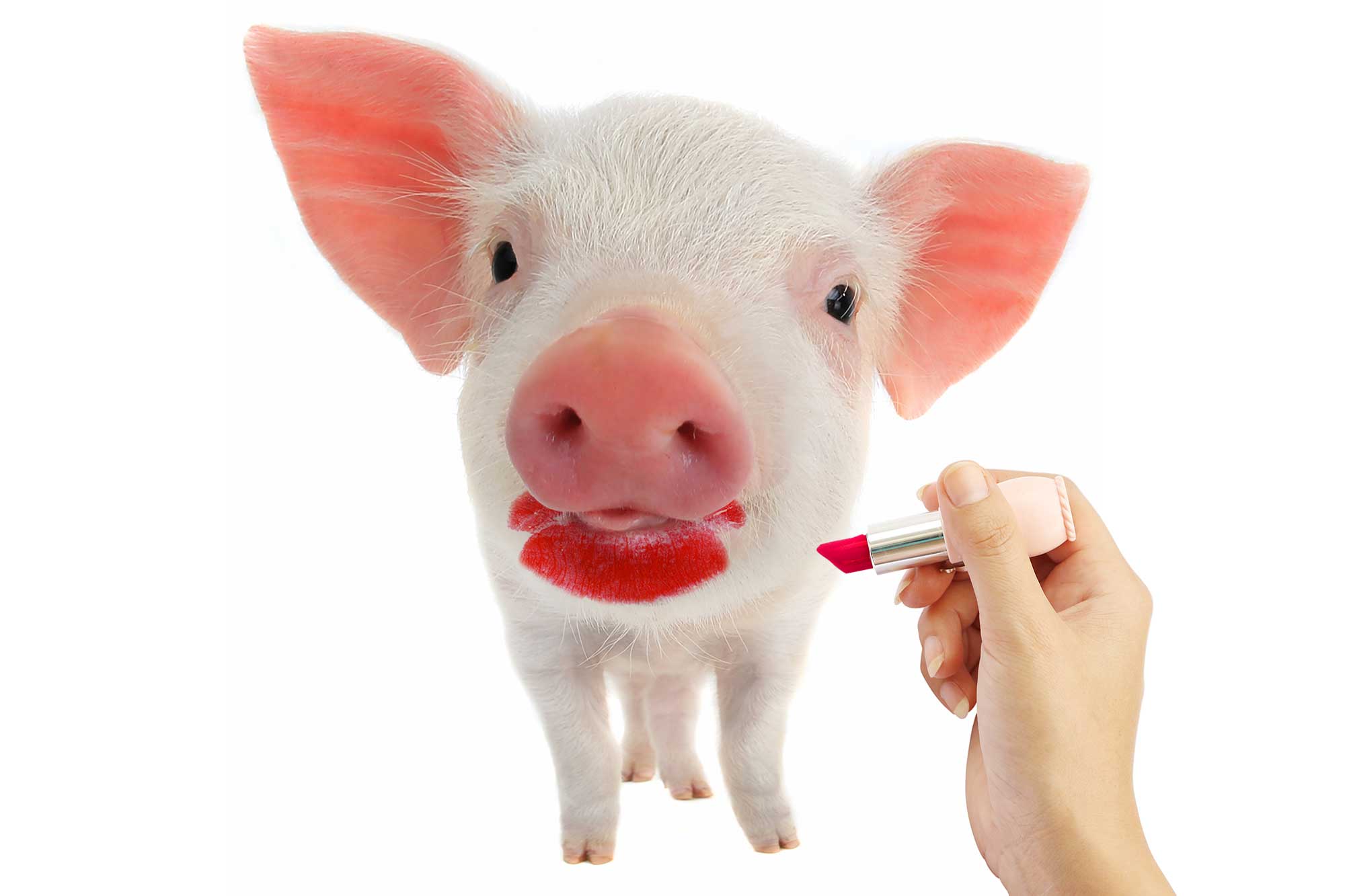

They try to pretty-up the need, to make it “acceptable” to the donor – as if that were an important value.

Jeff and I did a webinar last year where we were talking about taking the donor to the need through words and pictures. There was a picture of a malnourished child in our presentation. A person listening to and viewing the webinar objected to the picture, stating: “That’s so horrible. Why do you have to show that picture?”

Hmmmm.

Could the reason be because it’s true? Could it be that kids are suffering here in our country as well as overseas, because of the injustice of the systems they’re in? Could it be that this kind of truth is so hard to take that we just don’t want to see it? Of course it is.

Have you ever been in the presence of a starving child? I have. In Bangladesh. And in Africa. And with the garbage-pickers of the Philippines. And in South America. I’ve been in their presence. And it rips your heart out. It’s very, very difficult. It is not a joyful walk in the park. It’s dark. It’s disturbing. It makes you angry. The memory keeps you up at night.

It’s all of those things. And it is one more thing. It is true.

Why do we struggle with the truth of need?

The fact is that cancer is a devastating thing. So is being homeless. And being put in prison unjustly. And not having an education is hurtful. And having a polluted lake, or an abused animal. I could go on and on through every cause of every non-profit. The fact is that the needs addressed by non-profits run the range of sad and needless to devastating.

That’s the nature of need.

But we just have to pretty it up. Jeff’s and my business partner Carter Wade reminded me of how the insiders do this:

- “Don’t use the word extreme to describe poverty.” What!!?? And if it IS extreme poverty, how should we talk about it? “They were suffering from a little poverty. Nothing serious. It was just a tiny bit.” Really?

- “Don’t use underlining or bold to accentuate words. It makes things look too urgent.” Oh, so what you’re doing isn’t urgent? The need can wait until next year? Really?

- “Don’t show an image of the problem. We want to focus on the solution.” Oh boy. This is really messed up. So, you’re telling your donor that the thing is already taken care of. Not to worry, donor, we have it handled! No need to bother you with the need or the problem. I know it’s embedded in your heart and spirit as something you want to address. But we’re not talking about YOU, the donor. No, it is about us. WE feel uncomfortable with the need.

And there are many more examples. It’s a fatal disease that many authority figures and fundraisers have. Frankly, we don’t understand why these folks are even in the non-profit sector. A non-profit is where you band together with like-minded folks to solve societal problems.

One thing Jeff and I don’t expect you to do is get comfortable with the need your non-profit is addressing. Nope. You should never do that. It’s not a goal or a value. The need should always “bother” you. It’s a problem that needs a solution.

You should never get comfortable with the need. But you SHOULD get comfortable talking about it truthfully. Why? Because that’s your job. To truthfully and faithfully represent the problem to the donor – and then ask them to help solve it. (Tweet it!)

Don’t forget this. It’s critical to your success. And even more importantly, it’s what your caseload donor needs.

Richard

I love this post because I agree that we too often whitewash how difficult the problems we’re trying to address actually are. If a situation is urgent, we should call it such. If a family felt desperate, we should say that. In order to draw our donors closer to understanding our participants’ experience we owe it to them to detail honestly the magnitude of the problems our participants face. I also try and ask myself, “How would I feel if I experienced________?”

That said, I think the other side of this coin is that it can be easy, when describing the problem(s), to unintentionally cast those we serve in a less than flattering light. By saying a family is “desperate” we can also unintentionally imply they have no agency or capacity to address the problems they’re facing. If we neglect to highlight the assets our participants come to us with, we can, unintentionally, reinforce harmful stereotypes about vulnerable populations.

When communicating with our donors it’s important to be honest but I think it’s just as important to understand the power, and therefore implied authority, we wield as we’re sharing others’ stories, and that “being honest” should mean sharing the whole story – assets as well as difficulties.

I understand what you are saying but think consideration of what is shown is more than one perspective. If you see a hungry, malnourished child, I think that child is being used to raise money. Perhaps showing environment is less personal. The feeling created when seeing really sad or inhumane situations doesn’t always bring forth the desire to help. I have watched an ad to raise money for really poorly treated animals and I shut the tv off because it is too painful. Focusing on the value of helping engages an inspired response. It creates the desire to create change and make it better. The mission isn’t lost by not watching the discomfort of an abused child. It is knowing they can help with their gifts and what the gifts will create.

Amen. Straight-forward plain-speaking of truth is ALWAYS the best approach. We should neither “pretty-up” the truth nor “dirty-up” the truth. When agencies “dirty-up” the truth, making reality seem far worse than it is, they create so much distrust.

I first saw the devastating results of this in an agency I served 35 years ago which advertised a “Year-end Funding Crisis” only to rejoice 2 weeks later that they “made a profit” last year. The crisis was a lie because the agency refused to book annual interest income (designated for use) until midnight on December 31. They knew when they put out their plea that they had plenty of money. I was foolish enough to tell a major donor to the “crisis” the truth. Not only was he enraged, he went on a crusade forcing the agency to come clean about all of it’s resources. Thankfully, the agency made the change, but inside leaders were furious, claiming that we never know when “what if” might happen. They were “hiding” about $2,000,000 in resources.

In December last year an agency in our community sent out a similar plea claiming donations were not as they had budgeted. I know the agency always underspent their budget by significant sums. The executive is a frugal and tight money manager, which had some great benefits. This is why I found the appeal language interesting. Of course, the agency does not practice transparency, so it would have been a waste of my time for me to ask. It’s hard on donors who are passionate for a cause and are willing to give, but know they cannot trust the agency.

To “Pretty-up” or “Dirty-up” the truth is the same sin and hurts our work.