You know it’s true – you will be more successful if you have something specific to present to your donor. But Jeff and I hear over and over, in most every nonprofit we visit, that program specifics are hard to come by. If it’s not the program people, then it’s finance. And if both of them are cooperative, then the problem is in development, where no one is tasked to get the information.

The net result is that the MGO has to go to the donor with a bucket of air and try to convey the vision for how her giving will make a difference. Pretty sad, and very frustrating. Jeff and I see hundreds of major gifts officers in this position – MGOs who are not properly supported to do their major gifts job.

This topic is so interesting to me because it is so obvious yet so elusive. In a commercial transaction, there is hardly anyone on the face of the planet that would part with a lot of money for a nebulous promise. When we are going to buy something, we study the product benefits and features, we compare those benefits and features to similar products, and we carefully examine the opinions and reviews of experts and users.

We don’t just hand over the money! So why do we expect donors to do that? Perhaps this line of thinking is left over from the past, when a nonprofit would just say: “You know who we are. You know we are trustworthy. Trust us with the money. Just give.” This is last-decade (almost last-century) kind of thinking – where you are told just to shut up and give, and everything will be OK.

This does not work anymore. Donors want and need to know specifics. This is a fact. And the old time organizations who hold to the “trust us” view need to move into the present day of facts and specifics.

Jeff and I are actively trying to support MGOs – and major gifts in general – by helping management see that more needs to be done in this area. So here, in five relatively easy steps, is how you can be part of changing this in your organization:

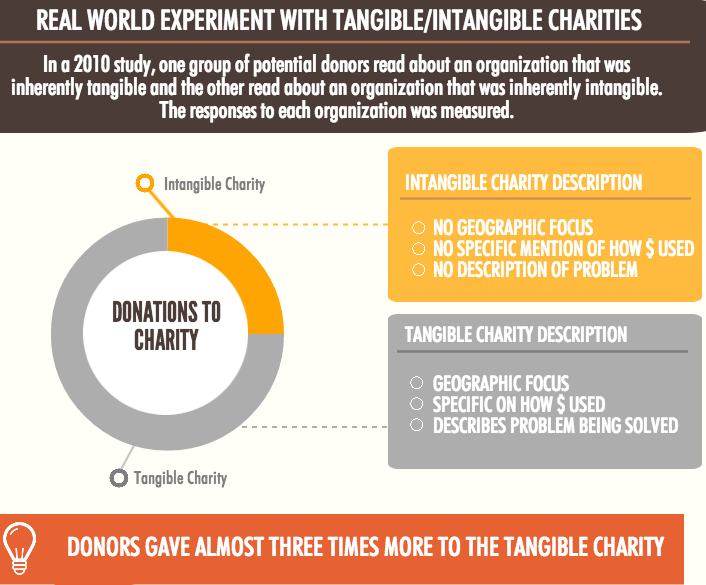

- Get familiar with the facts. The book The Science of Giving illustrates how specifics actually make a huge difference in fundraising success. These facts were brought to my attention by Brady Josephson, one of my favorite writers, philosophers and strategists on fundraising. He is the creator of the infographic I have partially reproduced and included at the top of this post. Go to Brady’s site for his complete comments on this subject. The bottom-line facts are simply this: donors give more to charities that give specific information on what the problem is and how money will solve the problem. This is a fact. So file away this fact for future use.

- Collect information on donor offers that are rejected. You know the drill. You have decided what to present to the donor. You have had difficulty getting specific information. But you move ahead and present the best case you can, which is general and non-specific. The result is a “no.” Document that event. Write it up.

- Collect information on donor attrition. When a donor on your caseload goes away, and you have asked why and they have told you that they did not know if their giving made a difference, you can conclude that (a) you didn’t tell them their giving made a difference, or (b) you did tell them, but the information was so general that it was not satisfying. It is this latter point you need to document.

- Calculate funds lost because of lack of specific information. You have documented the “no’s” and the donor attrition. Just add up the giving that has gone away from these donors or the opportunities that have been lost. In most cases like this, Jeff and I see losses somewhere between 30-60% of the annual caseload value – not a small sum of money.

- Take this information to your manager and make the case for spending more time and money on securing specific information for donors. This will be needed on the front end (offer creation) and on the back end (outcome reporting).

Hopefully, if you have an enlightened manager, the case you build and present by following these steps will make a difference, and he or she will institute a system (labor and infrastructure) to solve the problem.

Richard

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks