“I should get credit for that planned giving commitment,” said the Planned Giving Officer (PGO).

“No, you shouldn’t,” said the manager. “And here’s why.”

And then the discussion, sometimes an argument, starts. It’s a difficult path for any manager, as well as the PGO. What’s a reasonable and fair way to evaluate PGO productivity, effectiveness and performance?

I asked our Director of Planned Giving Services, Bob Shafis, and he gave me the answers I needed, which makes up most of the content of this blog. Thank you, Bob.

But before I get into the details, which I think you’ll find fascinating and thought provoking, I want to explain the philosophy Jeff and I, and our team, operate under as it relates to accountability and performance evaluation.

It’s summed up in the following phrase: a person will get credit for any result THEY caused that is measurable and verifiable. That’s it. So if you’re a MGO, you have a caseload of qualified donors and you have activity directed toward each donor; if that activity caused a gift and is verifiable, then you get credit for that gift.

The same applies to planned giving. The PGO has activity directed toward a donor. That activity causes a pledge of a gift or an actual gift. The pledge or activity is verifiable. The PGO gets credit for it.

But that’s not how a lot of planned giving reporting actually happens. Everyone in fundraising leadership needs to periodically review actual completed reports from planned giving staff to determine how productive they’ve been and how accurate their reports are.

Often planned giving results are misleading where gifts or pledges are reported for the following reasons:

- Gifts of unknown value reported at an unrealistically high value or using other methods (such as Zillow) to estimate a value which is really unknown.

- Gifts have little or no verification but are still reported as completed.

- Gifts are revealed by professional advisors who tell you neither the name of the donor nor the amount of their gifts.

- Gifts are reported which are unconnected to the actual fundraising work done by the reporting staff.

- Surveys are conducted and value is attached to donors who say they have included the organization in their will.

And many more items like this.

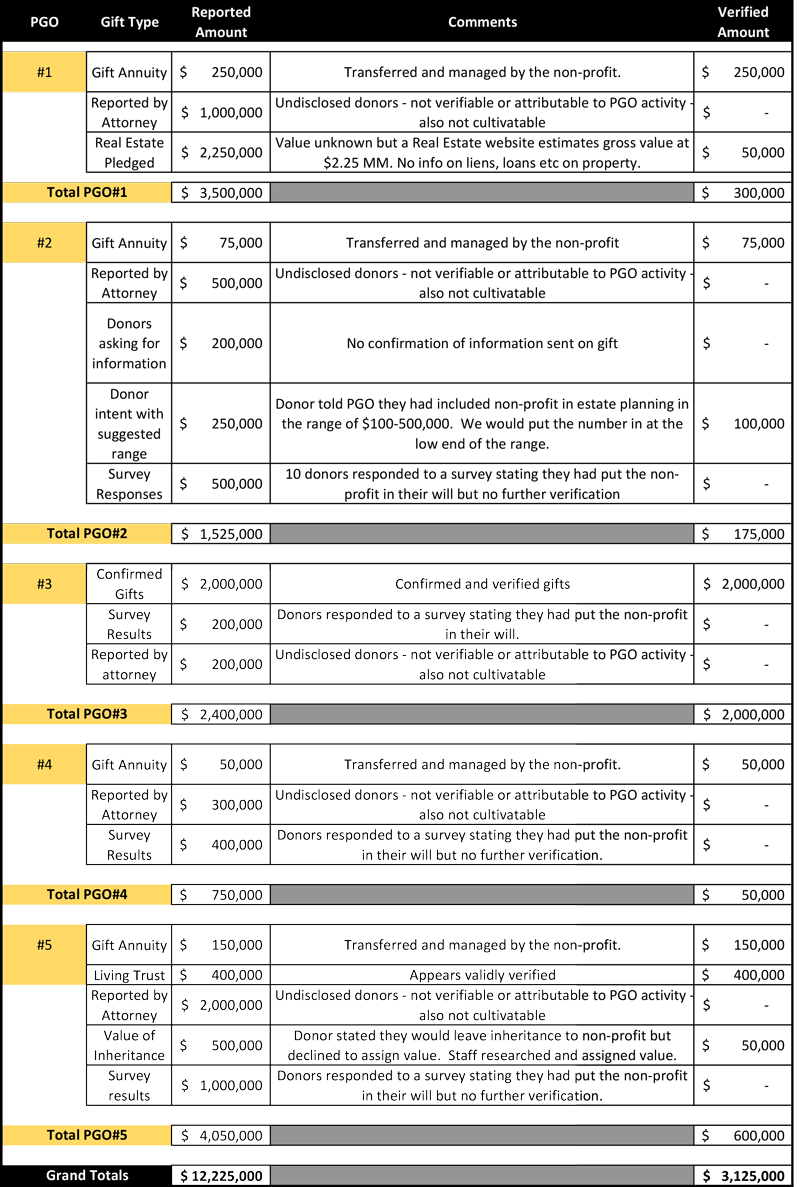

All of this results in Planned Giving staff wanting and taking credit for activity or situations that are not attributable to their work and/or not verifiable. And this kind of environment results in reporting like the real-life example (disguised to protect the source) Bob put together, which is replicated below.

Please note that there are five PGOs, and they are reporting their amount of production in the third column from the left, of which Bob is saying only a portion is actually verifiable or attributable to their work (that last column on the right). The result is that this planned giving team reported production of $12,225,000, of which we are saying only $3,125,000 can really be taken credit for!

This is a huge difference. Read the notes, by each entry, for our reason for disqualifying the credit.

So, how do you repair a situation like this? Here’s Bob’s answer in this list of elements one needs to use to evaluate how well their planned giving staff members are performing:

Types of Gifts

The organization needs to have clear standards about which gifts are reportable by planned giving staff. You need to know which gifts are being reported by the planned giving staff as planned gifts, and which other types of gifts are being credited to their work. For example, in addition to deferred gifts of both the revocable (wills, beneficiary designations, etc.) and irrevocable (gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts, etc.) types, are your planned giving officers also reporting direct gifts, donor advised funds, IRA QCD distributions, endowment funds, or even matured and distributed bequests?

You should know which gifts are acceptable and which should be reported elsewhere, since they aren’t planned gifts within your system. Direct gifts may be acceptable in some circumstances, but allowing planned giving officers to report matured bequests tends to be an area of abuse since they had nothing to do with causing the gift.

Valuation of Gifts

Since most planned gifts will take place in an uncertain time in the future, your organization needs to be clear about what value is to be reported, and then to make sure that method is followed consistently. Most often the gift is reported at the value shared by the donor ($100,000, for example), although some organizations calculate the present day value (most often a lesser amount based on the life expectancy of the donor).

Problems often arise when the donor won’t or can’t report a value, often because the gift is the percentage of an estate value in the future. Many charities choose an amount to assign as the value, either an arbitrary amount ($50,000 is the value used by the charity in the example above) or the amount historically received by the organization. This is acceptable but must be watched carefully to prevent abuse. Research shows that a reasonable range of values to project charitable bequests is $40,000-$70,000, although many organizations have a historical value below $40,000.

A related practice is to report the gift value after doing some research (such as Zillow) and allowing the gift of unknown value to be valued using an estimate of the donor’s estate. This converts a gift of unknown value to a gift which is usually wildly inflated.

Confirmation of Gifts

Once a gift has been revealed by a donor, most organizations have some standard to be met before a gift can be reported for credit. This takes the form of documenting the gift in some way.

The charity ideally would like to have a copy of the gift document, or at least the section showing the gift to that charity. Many donors won’t share that data, but confirmation in the form of a letter (or e-communication) from the donor or counsel will suffice. Also, a confirmation letter or email from the planned giving officer to the donor, giving the donor a chance to correct the information, may be used.

Increasingly, communication by a professional advisor to the planned giving officer can be abused, when they reveal that they have a client or clients who have left the organization in their plans. This is taken by a PGO at face value and reported at the assumed value used by the charity. This occurs even though the advisor cannot reveal the names of the donors because of confidentiality. A planned giving officer will sometimes report this information as if they generated the gift, while the charity is unable to recognize or steward the donor. These “Ghost Donors” can often end up as a major part of a staff person’s reported closed gifts.

Work Product

Are the reported gifts the result of the staff person’s activity? In order to evaluate the effectiveness of staff, the reported gifts need to be those cultivated, solicited and closed by the person reporting the gift for credit. Otherwise, the gift report is simply a tally of gifts the staff member has learned about from a variety of sources. Clear rules on crediting should be implemented to evaluate staff performance. This leads to being able to determine cost effectiveness of staff and program.

We recommend that you meet with each planned giving officer and review each reported gift to clarify:

- What kind of gift or pledge is reported, and what relationship is there between the actual work of the planned giving officer and the gift or pledge?

- How the valuation of the gift/pledge was determined, especially if the actual value is unknown?

- Was the gift/pledge valued using research or other data?

- If an assumed amount was used, is it a realistic number for the charity, or is it too high a value?

- How was the gift/pledge confirmed?

- Is there documentation?

- Was the gift/pledge disclosed by a professional advisor?

- Did you get the name of the donor or is it confidential to the professional advisor?

Jeff and I know this is a bit complicated. But it’s very important to make sure you properly evaluate the productivity and performance of each planned giving officer.

Richard

There are a couple of issues I see with your approach. First, how do you place a value on stewardship? The effects of good stewardship are invisible at times, but there is absolutely NO substitute for it. Example: I have stewarded our relationship with Mr. Jones for 10 years, moving him from a $100 donor to five-figures gifts on a regular basis (I know you guys don’t like the word “annual.”

Every time I try to talk about estate planning, he says, “My estate plan is set in stone and I’m not changing it.” When he dies, we receive $100,000 from his estate. Do I not get credit? If not, is it because the donor chose to keep his estate plan close to the vest? In my view, I’ve done my job well and the donor’s decision to leave us in his will is a direct result of my efforts.

The second issue is current vs. future valuation of the gift. Example: I ask Mrs. Smith to include us in her will and she agrees to leave us 1,000 shares of stock in ABC Corporation. The current value of the stock is $50,000, however, when she passes away, the stock has increased in value to $75,000. I only get credit for the $50,000? On the flipside, if the stock tanks and is only worth $25,000 when she dies, do I still get credit for the $50,000 or only $25,000? Now my performance depends on the whims of the stock market?

The last issue is “inherited donors.” MGO Jack gets a documented planned gift commitment of $1 million from a donor, Mrs. Adams. Jack leaves the organization 6 months later and MGO Stacy “inherits” Mrs. Adams’ and begins to steward and grow the relationship. Stacy grows the relationship for 10 years during which Mrs. Adams gives very little because, as we’ve all heard, “she doesn’t want to outlive her money.” When Mrs. Adams passes away, does Stacy get ANY credit for her 10 years of stewardship? If Stacy hadn’t continued to steward the relationship for the past 10 years, are we absolutely 100% sure Mrs. Adams would have kept the organization in her will or would she have felt slighted, ignored and forgotten and, as a result, decided to change her will and leave the organization NOTHING?

I checked in with our Planned Giving Services Director, Bob Shafis, and here are our answers.

On your first issue regarding stewardship, we agree. You did steward the donor and you should get credit. We are not arguing against stewarding donors; we are indicating that should not be what the planned giving officer spends their time on. Stewardship of donors who have made planned giving commitments should be done by a Planned Giving Associate (PGA) not the PGO….it is a waste of the PGOs time. Organizations should have a separate path for stewardship so that donors feel closely connected to the organization, and so that they continue with their gift commitments.

Here is the other thing – not everything will and should be counted in terms of planned giving work. There are so many uncertainties and differences in valuation that when dealing with the reporting of those gifts by staff, you have to make some hard decisions as to what will be reported and what won’t be. So, it is about setting up the credit criteria at the beginning.

Having said that, there are many ways of determining how to report bequests about which you don’t know the value. It is Bob’s opinion that it is best to choose one standard, realistic, amount, and allow that to be reported once. If the donors gift ultimately ends up being more or less than that amount, things should all balance out.

On the second issue of current vs. future valuation, the gift should be reported at a realistic value at the time that it is created AND be the work product of planned giving staff. If the gift ultimately becomes more or less, the credit would only be given for the time that it was reported. It is our opinion that the value assigned AT THE TIME of creation is the value that is reported, not some future value.

On the last issue of “inherited donors” – It is our opinion that the PGO gets credit for what they caused to happen. So, in your example, Jack, when he was with you, got credit for the $1 million, i.e. for writing it. Now the credit is done. The stewardship function should not be done by Stacy the MGO as the donor does not qualify as a major donor as relates current giving. That is a misuse of the MGOs time. Instead, the donor needs to be stewarded by the PGA (see above). To be clear, Mrs. Adams absolutely needs to be stewarded, but not by the MGO (since there is no current giving) and not by the PGO, since the PGO should be spending his or her time cultivating other donors.

Once again, we think these rules require some thought, and sometimes some flexibility, but they should be realistic and operate in a way that recognizes what the staff person has actually produced and can documented.

Remember, a Planned Giving Officer should get credit for what he or she actually caused to happen. This means what they actually WRITE in a given year, not what comes in years from now. Secondly, stewardship of donors who have made a planned giving commitment should be done by a Planned Giving Associate, a person dedicated to that function.