#2 of the series How a Caseload Grows Over Time

In my last blog, I talked about your major gift caseload as an incubator for transformational giving. Here is how that works.

In our training on building a caseload, we talk about qualifying donors so that you identify those high giving high capacity donors who actually want to relate to you. We also recommend you tier those donors “A, B, C” to signal that some donors have higher giving and higher capacity than others. This is so you know how to focus and prioritize your time.

Once you have done these two things – qualifying and tiering a caseload – it is important to step back and look at your caseload as having two large strategic functions:

- A mega-donor identification pool that is self-liquidating – This is that baseline or core part of the caseload that generates current revenue and where donors are retained and upgraded at ever-increasing rates. It has the most donors: 95% or more of the caseload. It is that part where all you know, when you are starting out, is what their current giving and their current capacity is. You don’t know much more than that, other than their passions and interests and communication preferences. This is all good news, because now you have a pool of good donors who are with you, who love the cause you represent, and from whom you will identify those few who will give transformationally. Now you have the time and opportunity to “roam around” this pool looking for those donors who want to do more. And you will be doing this work as the pool is contributing solid net revenue to the great cause you represent; that’s why I say this pool is self-liquidating. There is no additional cost to doing this. It actually pays for itself.

- A small group of mega donors – As time passes and you get to know your caseload donors, you will find those donors who can and will contribute more – who will make transformational gift. Jeff and I have seen this happen over and over again. A $1,000-a-year donor gives $1 million. Or a $5,000-a-year donor gives $12 million over two years. Or a $10,000-a-year donor gives $1.3 million over two years. We have scores of examples of this dynamic. But here’s the thing: these donors didn’t suddenly just do that. No. The MGOs worked with their pool of donors, got to know them all and proactively looked for these donors. I say “proactively” because while you are managing your caseload, you need to be actively looking for the donors who will join you in this way.

The reality of a caseload is that most of the donors on it will only upgrade so much. You cannot expect every donor to give substantial gifts. In fact, your economic objective on the caseload falls into 3 areas:

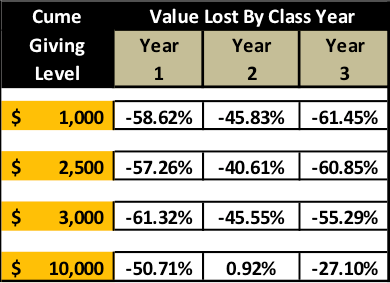

Reduce value attrition – this is the amount of money the same donors give every year. Remember, in most organizations that don’t have a functioning major gift program, this loss is a staggering 40-60% per year! In fact, in a study we did of 33 national organizations this is what was lost every year from donors who gave at four different levels. Just look at this chart and multiply the cumulative amount the donor gave in that year, then subtract the percentage that is showing to the right of that amount. It will quickly dawn on you that money is flying out the door. So, one economic objective is to reduce this. And you will, over time. It will turn positive because you are now truly serving the donor and her passions and interests.

Reduce value attrition – this is the amount of money the same donors give every year. Remember, in most organizations that don’t have a functioning major gift program, this loss is a staggering 40-60% per year! In fact, in a study we did of 33 national organizations this is what was lost every year from donors who gave at four different levels. Just look at this chart and multiply the cumulative amount the donor gave in that year, then subtract the percentage that is showing to the right of that amount. It will quickly dawn on you that money is flying out the door. So, one economic objective is to reduce this. And you will, over time. It will turn positive because you are now truly serving the donor and her passions and interests.- Reduce Donor Attrition – this is a cousin to reducing value attrition. While you are doing the good work of reducing value attrition, the number of donors who actually go away will also be reduced.

- Upgrade Donor Giving – Lastly, donors who are properly served, who you have treated as partners and not just sources of cash, will actually give more.

While all of this is happening, you will be finding those few donors in the caseload who will give a transformational gift when you ask them to. So do two things from this day forward. Keep treating all of those good donors on your caseload with respect and care – looking for every opportunity to serve them outrageously and fulfill their interests and passions. And lastly, always be looking for those few who can and will do substantially more.

Richard

0 Comments