In my last blog, I talked about that delicate and interdependent relationship of org structure to the donor pipeline, which needs a great deal of care and feeding. That discussion naturally leads to the question Jeff and I are always asked:

“How much should I be investing in the major categories of fundraising in our organization?”

The question prompted me to create some general guidelines on how to think about your fundraising budget. So, take a few moments to go through the process I’ve outlined here. It will help focus your planning.

The first step is to organize your fundraising strategies into three major categories:

- Direct Marketing Programs.

These are acquisition, cultivation, and online strategies. There may be more than these three in your organization. The way you decide if it goes here or not is to determine if it’s a direct marketing program. If it is, then put it here.

- Relationship Fundraising Programs.

These traditionally are mid-level, major, and planned gifts plus grants.

- Events and campaigns.

You may have exceptions to this list – for instance, earned revenue like ticket sales, or where folks pay a fee for a service the organization provides, like the Y and its membership for the fitness program, or a secondhand store, like Goodwill or The Salvation Army store, etc. Or the gifts in-kind area where you are working to secure gifts in-kind for the organization.

All of these are revenue sources. The reason I do not include them in this exercise is because they have their own stand-alone economies which govern the investments they get. And while they may have some relationship to the donor pipeline – you can and will solicit ticket buyers, clothes buyers, fitness members, etc., for donations – they will not be a primary and effective source of valuable donors.

Now that you have organized your fundraising strategies into categories, do the following:

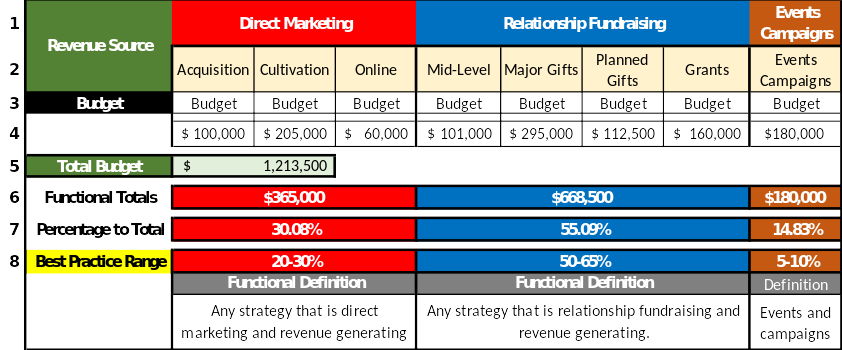

- Replicate the chart below and put the categories in Row 2.

- Enter the budget for each revenue source for the year in Row 4.

- Sum up all the totals and enter the total budget cell in Row 5.

- Add up functional totals and enter those totals into functional total in Row 6.

- Calculate the percentage of the functional total to the total budget and enter that in Row 7.

- Compare the best practice range in Row 8 to your total in Row 7 and determine if adjustments are needed. Note that in the example here, the events total is too much and needs to be adjusted downward to be in the 5-10% range of fundraising spend.

Now that you have done this exercise, here are some questions that may come up for you regarding your fundraising budget, and our answers to those questions:

-

Why do you have a higher spend for relationship fundraising than you do for direct marketing?

Because the relationship fundraising strategies deliver higher ROI and net revenue.

-

What if we want to grow more than we have been growing – doesn’t that mean that our spend in acquisition and cultivation will be higher?

Yes, it does. And those are the kinds of decisions you make that are informed by what you are trying to do with the donor pipeline. Our point in this exercise is to help expose you to the need to deal holistically with the pipeline within the context of overall organization revenue, growth objectives, and ratio (overhead vs. program) objectives.

-

Why are you putting the events spend so low? Events are a major part of our fundraising.

Jeff and I feel strongly that the way most non-profits think about and approach events needs to change. There are many organizations out there that have leaned into event-based fundraising as their primary fundraising effort. Now, events can be beneficial and do bring in some revenue, but the challenge of events is that they typically don’t have a great ROI and are often transactional. Yet, organizations are spending a lot of time and effort on something that doesn’t have a great impact in the long run.

When events, major gifts, and all other fundraising disciplines are not in partnership together, the departments may also be “competing” over donors because there’s no structure for collaboration. When there is a clear system and structure for how to use events as part of your fundraising efforts, the event better serves its purpose, as a marketing / PR / brand enhancement or cultivation effort, and this collaboration will drive even more revenue to support your mission. Remember, donor relationships are dynamic. Your donors may want to engage with you in a wide range of ideas. It’s critical not to limit the donor or put obstacles in the donor journey. Your goal is to achieve a more relational approach to fundraising that better serves your organization and your donors and to use events appropriately as a vehicle to achieve this.

-

What if we want to grow our major gift program, but we don’t have enough donors to do it, nor do we have the resources to invest in donor acquisition?

This situation is not unusual. Jeff and I face this dilemma all the time. And although there is a solution, it’s not an easy one. There is no doubt that you must invest in donor acquisition to “feed” the donor pipeline so you can have a successful major gift program. You either must find the money to invest in donor acquisition, or create a business plan to acquire donors (an effort that a donor will fund). We have done this before, and it does work. There are donors who find it more fulfilling to help fund the acquisition and care of donors than to fund the program directly. Why? Because the donors they help acquire and cultivate will deliver more economic value than an outright gift will deliver. My point here is that you cannot expect to have a robust major gift program without addressing the need to acquire donors.

-

Are your percentages for spend really best practice?

In general, they are, but again it depends on the life cycle of the non-profit and the growth objectives you have. The best way to think about what I have presented in this blog is to use it as a general guideline for spending. This context will help you understand how to consider your fundraising spend within the context of the health of your donor pipeline and the objectives of your organization.

You may have other questions that are prompted by this exercise. Feel free to let us know what they are, and we’d be happy to answer them. But one thing is true.

You must have a rationale for what your spend is in the major categories of your fundraising budget.

And that rationale must be based on the health and the dynamics of your donor pipeline and your overall organizational objectives. Keep all of this in mind as you create your next budget.

Richard

0 Comments