It was an interesting conversation. I was taking the position that “meaningful connections” and amount raised are what matters in measuring MGO performance, and the manager was arguing that it was the number of face-to-face visits and amount raised. We were going back and forth on the subject with deeply entrenched beliefs supporting each position.

So I decided to look “out there” and see what others were saying.

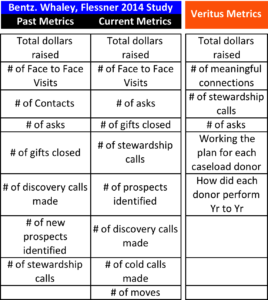

In a 2014 study done by Bentz, Whaley and Flessner on “Optimizing Fundraiser Performance” in the healthcare and education sector, the authors stated that the major gift metrics had changed (in priority and emphasis) from 2005 to present as reflected in the following chart:

Note that I have inserted a column on what Jeff and I think matters in terms of measuring MGO performance. More on that later.

Note that I have inserted a column on what Jeff and I think matters in terms of measuring MGO performance. More on that later.

Of interest to me is that the old face-to-face metric still is sitting there as an important measurement. The problem with the FTF metric is that it can be made to mean many different things. As one manager said to me recently: “the FTF thing can be gamed, Richard. A MGO, if they want to, can make that number really high.” It’s true. Or the MGO can meet with the same donor repeatedly, increasing the number. Or the quality of a “visit” can be really low and have no meaning as well, like the MGO that counted an encounter in a grocery store. Totally meaningless.

What really matters, in our opinion, is meaningful connections. What is a “meaningful connection”? It is one where the MGO has quantifiably moved the donor in the direction of fulfilling her passions and interests by giving to the organization. Quantifiably move? What does that mean? And “in the direction” – how do you know?

First, the MGO knows, without doubt, what the interests and passions of the donor are. You can measure that with a simple “yes” or “no.” Secondly, the donor has taken an action or said something that shows they are moving in the direction of making a gift. It could be as little as “you know, I really would like more information on that” or “yes, I would like to meet with your program person to learn more about the X program” or “can you send me information how that program actually works?” It could also be the acceptance of an invitation to attend a briefing or visit a program site.

Here is the important point in all of this: a meaningful connection can happen in a face-to-face, in an email exchange, on the phone and, yes, at the grocery store, an afternoon tea, a baseball game, etc. It is not limited to being literally face-to-face. A meaningful connection is when the donor takes an action or says something that shows interest – it is also fulfilling the move you have pre-planned for the donor.

Here’s the thing. You do know when you have come face to face with a meaningful connection. You also know when it isn’t one. Having said all of this, I think I will write a document that defines a meaningful connection more clearly for all those that may have trouble recognizing one. That’s later.

In a study published in 2010 by Bentz, Whaley and Flessner titled Major Gift Metrics That Matter, the author, Thomas W. Grabau, makes an important point that seems to support our position on metrics. He says: “All managed and assigned prospects (donors) should have a philanthropic capacity and connectivity rating.”

Capacity and connectivity. The word connectivity helps define “meaningful.” There is a connection. You know it. You also know when there isn’t one.

We agree on the capacity/connectivity point Grabau makes.

In our system of caseload development, the MGO is instructed to develop a caseload from a pool of donors who have given the highest amounts most recently and have the highest capacity. This is a confluence of amount, recency and capacity. The second big point in caseload development is that the MGO will only have qualified donors – donors who want to connect – on their caseload. This addresses the connectivity issue.

In that same study, Grabau addresses what he calls the “Rules of Thumb” of major gift metrics:

- There should be an average of 12-15 FTF visits per month.

- MGOs should visit approximately 50% of their caseload donors each year.

- Approximately 1/3 of a MGO’s caseload should be in the solicitation stage.

- A full-time MGO should raise $1 million a year on average.

Take a look at his study to see how he addresses each of these points. There is some very good and useful information there; and although we take a different direction on FTF visits (we think the MGO should connect with ALL the donors on her caseload), donors should be asked when they are ready – and the $1 million thing may be a good goal for a fully developed and mature caseload but not one just starting out. That could be as low as $200,000 – $300,000.

Here is how we would frame the important metrics in major gifts:

- First, the caseload should contain 150 qualified donors. This means no prospecting, and it also means that these donors want to relate – the connectivity point. There is no sense in paying a MGO to “work” donors that have “given a lot of money” but don’t want to connect. It is a waste of labor. I saw one situation recently where a MGO had over 1,000 donors on his caseload! There is no way he can connect with all of those donors. I’ll bet if we put those 1,000 donors through our qualification process only 250 would actually want to connect – and that would still be too many donors for the MGO to handle.

- Then there should be a goal and plan for every donor. This point is critical. This means that there is a predetermined intention on the part of the MGO to meet with, talk to and connect with the donor. This point, by itself, is a huge performance measurement point, answering the question: “did the MGO work the plan for every donor on her caseload?”

- Now measure the number of meaningful connections, stewardship calls, number of asks and how each donor is performing year to year. All these points are self-explanatory. The individual donor performance year to year is important. You want to know that the MGO has a “story” or explanation for why a donor gave less or didn’t give at all.

- And finally, make sure the MGO is working the plan. This “making sure” bit is why management of MGOs is so labor intensive and why most DODs just do not have the time, given everything else they have to do, to manage MGOs correctly. This is a controversial point for many development shops. Why should we hire or pay for someone to manage MGOs? The answer: because you will not do it. You need to spend a ton of time with every MGO going through every donor on the caseload to make sure the plan is being executed.

- All of this should be written up for each MGO’s performance evaluation. At the beginning of each year, once the caseload plan is done, you should write up the performance plan for the MGO – that list of items the MGO will be evaluated on – the points above this one. These are quantifiable, time sensitive items, which no one can argue with.

Grabau points out in his 2010 paper that the three essential elements for caseload management are:

- A clear understanding of the potential of caseload donors. We would add “qualified” caseload donors.

- Plans (for each donor) that drive results. This means there is intentionality on connecting with caseload donors. We would assume goals for every donor are in these plans and that the MGO knows why each donor has given less or lapsed.

- Execution – Is the plan being worked? Are meaningful connections being made with all the donors on the caseload?

Fundamental and central to all of this is the donor. Are you serving her needs? Are you fulfilling her interests and passions? You will be if you are connecting. And you will be raising money if you are doing all of this right. That is what you should be measuring – are you fulfilling the donor’s interests and passions?

Richard

Read the full series:

Who is responsible for qualifying donors if not a major gifts officer?

This is a great post. You are writing the bible on major gifts. The metric comparisions (past/current/Veritus) is enlightening.

I’m never disappointed with the posts from Veritus and find takeaways from everything posted. Thank you for your quality of insight and written expression. You are providing a great service to those of us who are major gifts officers. Well done!