Where Are Your Boundaries with Donors?

If you’ve been following this blog for any length of time, you know we talk a lot about building meaningful relationships with donors. Why? Because...

I remember when I was a kid, I broke one of my dad’s tools in the garage because I was playing around with it. I knew he would be mad because I wasn’t allowed to play with that particular tool. What did I do? I hid it so that he wouldn’t find it and know that it was broken.

“Whew,” I thought, “he’ll never know.”

And he didn’t know… and I went on my merry way doing kid stuff and forgot about the fact that I broke the tool.

However, about a week later, I was doing something in my room when I heard my dad’s booming voice, “Jeff, can you come out to the garage?” And, from the tone in his voice, I knew I was in trouble. When I went into the garage, there was my dad, holding the tool I had “hidden.” “Jeff, did you break this?” my dad sternly asked. “No, I didn’t do anything,” I said.

Of course, parents know when you’re lying, and I wasn’t very good at it. After a couple of more queries, I caved. “Yes, I broke it,” I said. My dad looked at me and said, “Look, you know you weren’t supposed to be playing with this, but the fact that you not only broke it, but hid it, really makes me upset and disappointed in you.”

Even more than the grounding I got, the shame I felt from the look on my dad’s face, was worse. Not only did I do something stupid, but I also hid it from him. Later, he would tell me that we all make mistakes, but instead of hiding it, it’s better to just own up to it. Good advice.

Why am I telling you this story?

Because when a donor-funded project or program is failing or underperforming, many non-profits try to pull a “young Jeff” move on them and hide the problem, rather than go through the pain of telling the truth.

Instead of being honest, non-profit leadership tries to conceal the problem because they fear the donor(s) will either never give again, or worse, pull their funding from the failed project or program.

Now, it’s possible that you could get away with not communicating to the donor that something they funded isn’t going as planned or is failing, but in Richard’s and my experience, you will not get away with it forever. It may take some time, but people are going to find out eventually.

That is why we always advise our clients and all front-line fundraisers we work with to tell the truth to their donor. Yes, we understand it’s painful and you will run the risk of the donor never giving you another gift. But when you tell the truth, and do it in a timely manner without trying to delay or hide anything, that truth sets you, the organization, and the donor free to move forward.

Whereas when you try to hide the truth, you’ll most likely lose the donor’s trust. Trust is not easily repaired if broken. It’s basically the worst thing that can happen to a front-line fundraiser.

Now, what do you do if you want to tell the truth, but you have others in your organization that don’t, like the program team, finance, or even leadership? First, they are putting you in a bad position. But if this happens, your job at that moment is to be an advocate for the donor. Help them understand how the donor relationship works. That if you lose the donor’s trust, you will lose the relationship and future funding.

Help those in your organization know that donors will understand that not everything you do works. Some ideas, projects, or programs just don’t work out. And, even better, if you can show the donor what the organization learned from the failure or mistake, that helps the donor even more. Donors know that we are human, mistakes happen, but, like my dad, they just want you to be honest about it.

In fact, something to say to a donor before they even make a gift is to tell them upfront, especially if this is a new project your organization is undertaking, that there is always the risk that it could fail. If your donor is smart, they will get it.

Now, if after all that, your management or leadership still tells you not to talk to the donor about a specific failure, our advice is that you must leave. That is a toxic work environment, and you don’t want to be part of lying or hiding things from a donor.

Richard and I don’t see a gray area here. If you cannot be allowed to uphold your own values and ethics with a donor, you can’t be part of that organization.

Hopefully, you never get to that point. Hopefully, you can foster an environment that values honesty, learns from mistakes, and doesn’t hide from failure. Learn from those failures and communicate openly about them with your stakeholders. In the long run, your honesty will create more trust and continue to inspire new investments in your mission.

Jeff

If you’ve been following this blog for any length of time, you know we talk a lot about building meaningful relationships with donors. Why? Because...

1 min read

If you have attended one of the many trainings of nationally recognized major gift gurus, you have likely learned many techniques and strategies on...

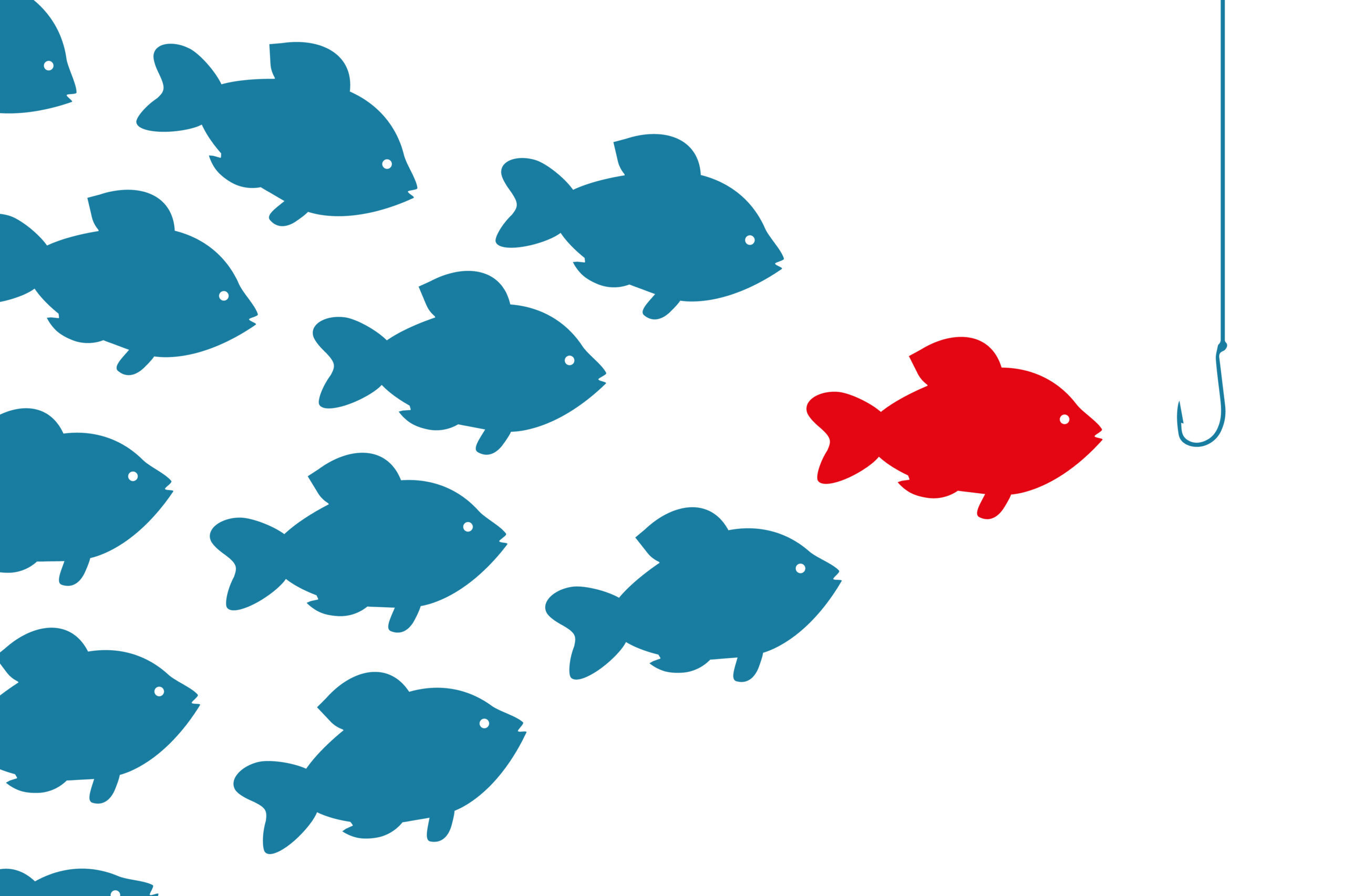

This is Part 2 of a series on building trust: “No Trust, No Relationship, No Money.” “The fish stinks from the head.”